Notepad++ Hijacked By State-Sponsored Hacker: What Happened and How To Hunt For Exploitation with ThreatResponder?

The recent Notepad++ incident is not a traditional software vulnerability in the editor itself. It is a supply chain style compromise where attackers interfered with how update traffic was delivered and verified, selectively redirecting a subset of users to attacker-controlled infrastructure that served malicious update artifacts. The Notepad++ maintainer describes an infrastructure-level compromise at the hosting provider that enabled interception and redirection of update traffic destined for notepad-plus-plus[.]org, with targeting that appeared highly selective rather than mass distribution.

From a defender’s perspective, this matters because the update channel is a high-trust path. Enterprises often allow software updaters through controls that would otherwise block unknown installers. In this case, older versions of the updater logic were a weak link: traffic to the update endpoint could be redirected and the returned update metadata could point victims to poisoned binaries. The maintainer notes the compromise window beginning June 2025, with hosting-level issues persisting in phases through December 2, 2025.

Security Risks: Why This Incident Is High Impact

A compromised update mechanism can bypass many common security assumptions. Users believe they are installing a legitimate patch. IT teams may not scrutinize the action because it is a trusted application updating itself. That combination creates ideal conditions for initial access, persistence, and follow-on intrusion. The incident update explains that redirection was limited to targeted users and that the attacker focus was specifically on the Notepad++ domain, which aligns with espionage-style tradecraft rather than opportunistic malware.

Independent threat research tied observed intrusions to a custom backdoor delivered immediately after Notepad++ execution and updater activity. Forensic evidence showed a repeatable execution sequence where notepad++.exe and GUP.exe preceded the download and execution of a suspicious update.exe from 95[.]179[.]213[.]0, which then staged the infection chain.

The Attack Chain Observed in the Wild

Stage 1: Trojanized updater flow to suspicious installer

Investigators were able to validate the process lineage end-to-end: Notepad++ followed by GUP (the updater) and then execution of update.exe downloaded from 95[.]179[.]213[.]0. This is important for responders because it provides concrete telemetry pivots even if the original malicious update manifest is no longer available.

Stage 2: NSIS installer drops payloads into a hidden AppData directory

Analysis of update.exe showed it to be an NSIS installer, a packaging format frequently abused in targeted campaigns. The installer created a %AppData%\Bluetooth directory, marked it hidden, and dropped multiple components including BluetoothService.exe, an encrypted payload named BluetoothService, and a malicious DLL named log.dll.

Stage 3: DLL sideloading via a renamed legitimate executable

The installer used BluetoothService.exe, a renamed legitimate Bitdefender Submission Wizard binary, to sideload the malicious log.dll placed alongside it. Exported functions within the DLL were leveraged to load, decrypt, and execute shellcode directly in memory, reducing on-disk indicators and complicating static detection.

Stage 4: Backdoor execution, C2, and operator capabilities

Once decrypted, the shellcode represents a feature-rich custom backdoor designed for long-term access rather than a short-lived dropper. Configuration data recovered from infected systems pointed to a command-and-control endpoint at https[://]api[.]skycloudcenter[.]com/a/chat/s/{GUID}, with observed resolution to 61[.]4[.]102[.]97.

The backdoor supports interactive command execution and file operations. Documented command tags include spawning an interactive shell (4T), creating processes (4V), writing files (4W and 4X), reading and sending data (4Y), enumerating files and drives (4` and 4_), and uninstall and cleanup routines (4\).

Stage 5: Post-compromise tooling and Cobalt Strike loader activity

Follow-on activity was observed involving a ProgramData folder named USOShared and an execution pattern calling svchost.exe -nostdlib -run with a C source file named conf.c, alongside libtcc.dll. This workflow aligns with the use of a renamed Tiny C Compiler to execute embedded shellcode that retrieves additional payloads.

Analysis of conf.c showed it retrieving content from api[.]wiresguard[.]com/users/admin, then decrypting and staging a Cobalt Strike HTTPS beacon configuration using http-get api[.]wiresguard[.]com/update/v1 and http-post api[.]wiresguard[.]com/api/FileUpload/submit.

TTPs Mapped to Defensive Concepts

This campaign blends multiple well-understood tactics into a low-noise chain.

Initial access and execution

Initial access occurs through supply chain abuse via update traffic redirection and installer delivery, rather than exploitation of a vulnerability in the Notepad++ application itself. Execution pivots on user or automated updater activity leading to a dropped installer, followed by process creation and in-memory shellcode execution through DLL sideloading.

Defense evasion

Multiple layers of obfuscation are used, including custom API hashing, encrypted configuration blobs, and runtime string reconstruction. The use of a legitimate renamed executable to load a malicious DLL is a classic sideloading technique intended to blend into normal application behavior and reduce signature-based detections.

Persistence

The backdoor inspects command-line arguments and, when run without additional arguments, installs persistence primarily through Windows service creation with a registry fallback. It then relaunches itself using -i and -k modes that separate installation from payload execution. A global mutex named Global\Jdhfv_1.0.1 is created to enforce single-instance execution.

Command and control and post-exploitation

Command-and-control communication occurs over HTTPS using a common browser user agent string, with encrypted host profiling data posted to api[.]skycloudcenter[.]com. Post-exploitation includes delivery of additional tooling, including Cobalt Strike, via a custom loader chain retrieving content from api[.]wiresguard[.]com infrastructure.

Practical IOCs and Hunting Pivots

Below are high-signal pivots derived from publicly documented analysis and the Notepad++ incident update. Treat these as starting points and enrich with your own telemetry.

Host-based IOCs

File system paths and dropped components

- %AppData%\Bluetooth\ (hidden directory created by the installer)

- %AppData%\Bluetooth\BluetoothService.exe (renamed legitimate executable used for sideloading)

- %AppData%\Bluetooth\log.dll (malicious sideloaded DLL)

- %AppData%\Bluetooth\BluetoothService (encrypted shellcode container)

- C:\ProgramData\USOShared\conf.c and libtcc.dll (observed post-compromise artifacts)

Mutex

- Global\Jdhfv_1.0.1

Process and command-line pivots

- notepad++.exe → GUP.exe → update.exe execution chain

- Malware modes using -i and -k command-line flags for launcher and payload logic

- svchost.exe -nostdlib -run C:\ProgramData\USOShared\conf.c

Cryptographic hashes for key files

-

NSIS].nsi:8ea8b83645fba6e23d48075a0d3fc73ad2ba515b4536710cda4f1f232718f53e

- BluetoothService.exe: 2da00de67720f5f13b17e9d985fe70f10f153da60c9ab1086fe58f069a156924

- BluetoothService: 77bfea78def679aa1117f569a35e8fd1542df21f7e00e27f192c907e61d63a2e

- log.dll: 3bdc4c0637591533f1d4198a72a33426c01f69bd2e15ceee547866f65e26b7ad

Network-based IOCs

- Download source IP observed for update.exe: 95[.]179[.]213[.]0

- C2 infrastructure: api[.]skycloudcenter[.]com with URL pattern /a/chat/s/{GUID}

- Observed resolution of C2 host to 61[.]4[.]102[.]97

- Secondary infrastructure for payload retrieval and Cobalt Strike:

- api[.]wiresguard[.]com/users/admin

- api[.]wiresguard[.]com/update/v1

- api[.]wiresguard[.]com/api/FileUpload/submit

What Companies Should Do Now

Immediate containment and verification actions

- Identify endpoints that ran Notepad++ updates during the compromise window spanning June 2025 through December 2, 2025.

- Hunt for the execution chain and file artifacts described above, especially update.exe execution following GUP.exe and creation of the %AppData%\Bluetooth directory.

- Isolate any endpoint with backdoor artifacts or connections to the listed C2 and retrieval domains, then perform full triage including memory analysis and persistence review.

- Ensure Notepad++ is upgraded using a known-good installer that enforces hardened update verification controls introduced in later versions.

Longer-term controls to reduce blast radius

- Treat third-party updaters as privileged software deployment mechanisms and enforce strict publisher and certificate validation.

- Centralize software distribution for common utilities to avoid unmanaged auto-updaters on high-trust endpoints.

- Monitor for DLL sideloading patterns, especially legitimate executables running from user-writable locations such as %AppData%.

- Build detections for staged post-exploitation frameworks, including loaders and Cobalt Strike–style beacon behavior.

How to Hunt Notepad++ Exploitation Using ThreatResponder

Threat Hunting Module: hypothesis-driven searches across the fleet

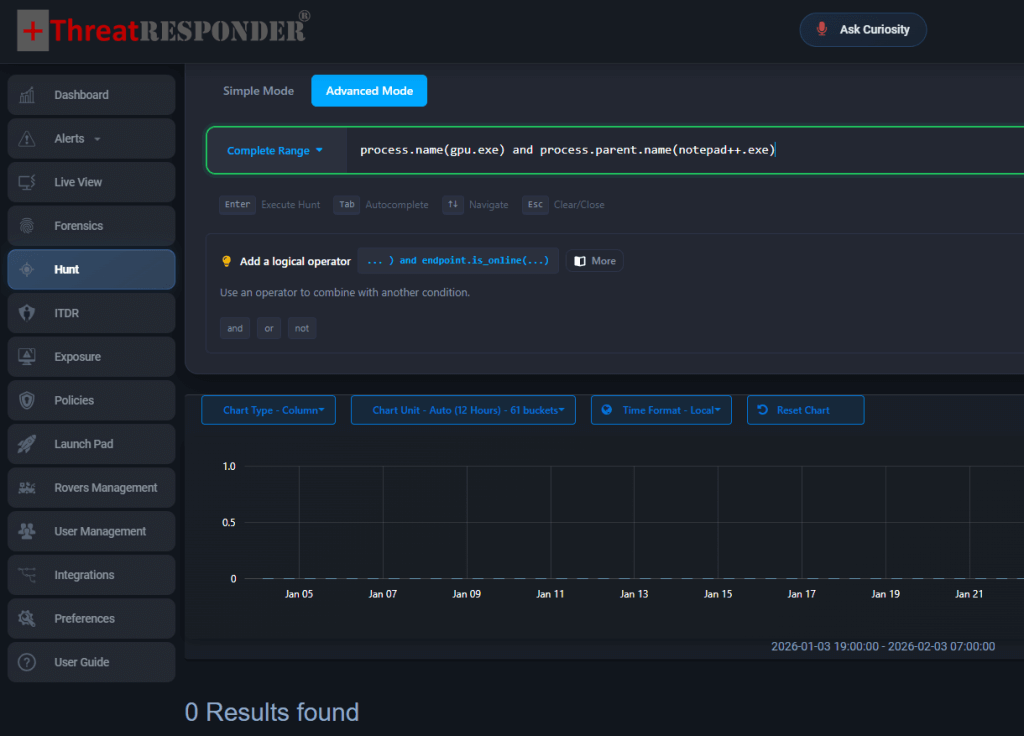

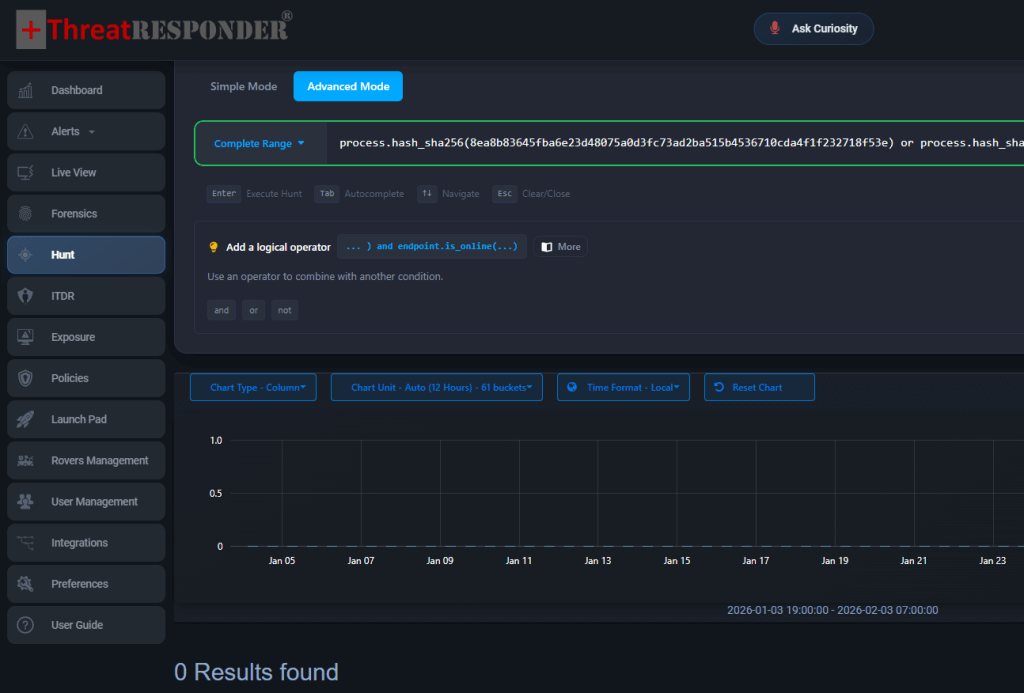

Use the Threat Hunting Module in ThreatResponder to operationalize both IOC-driven and behavior-driven hunts:

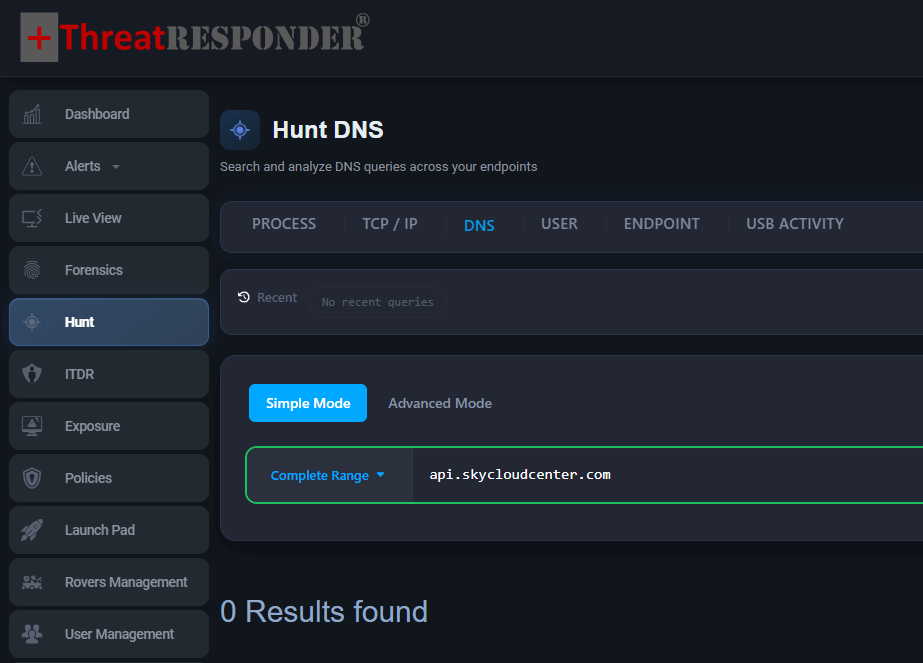

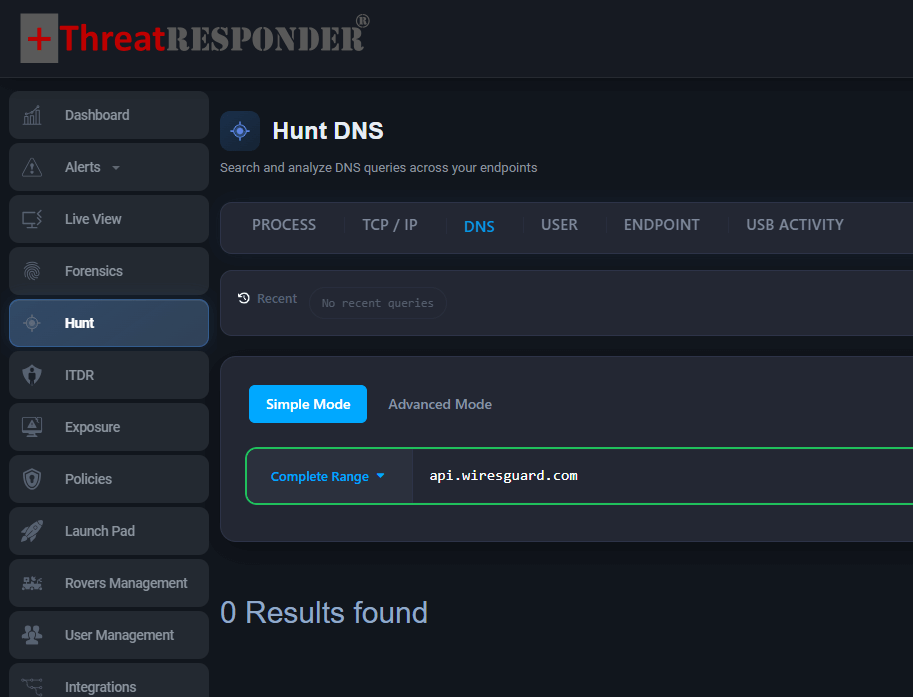

Hunt for outbound connections to api[.]skycloudcenter[.]com and api[.]wiresguard[.]com, pivoting into initiating processes and users.

Figure: Domain based Hunt for Notepad++ Exploitation with ThreatResponder’s Simple Hunting Mode

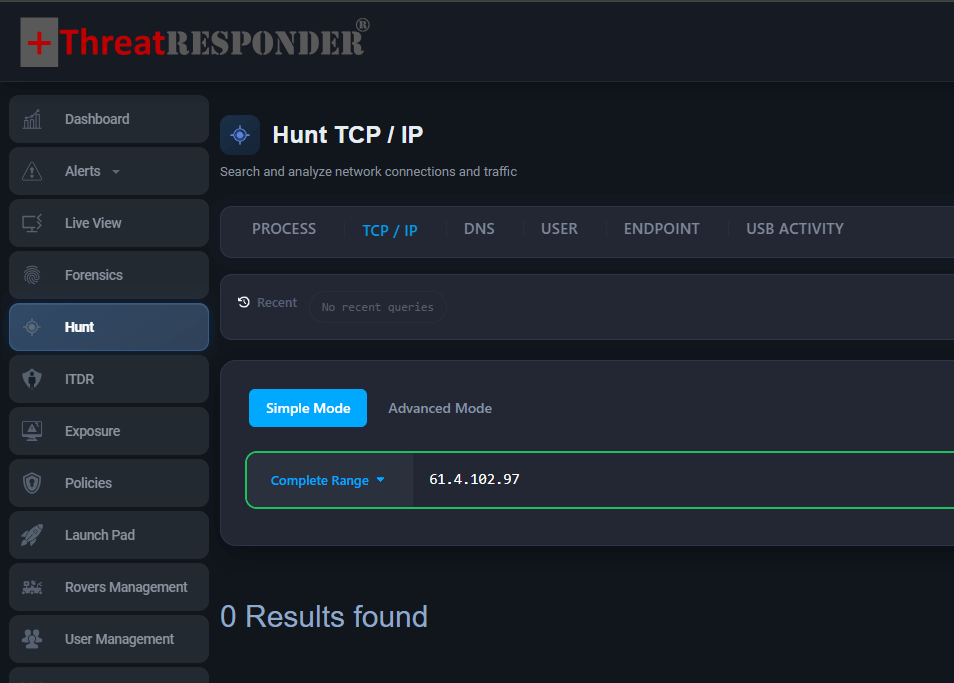

Hunt for DNS resolutions to 61[.]4[.]102[.]97 and historical connections to 95[.]179[.]213[.]0 tied to update workflows.

Figure: IP based Hunt for Notepad++ Exploitation with ThreatResponder’s Simple Hunting Mode

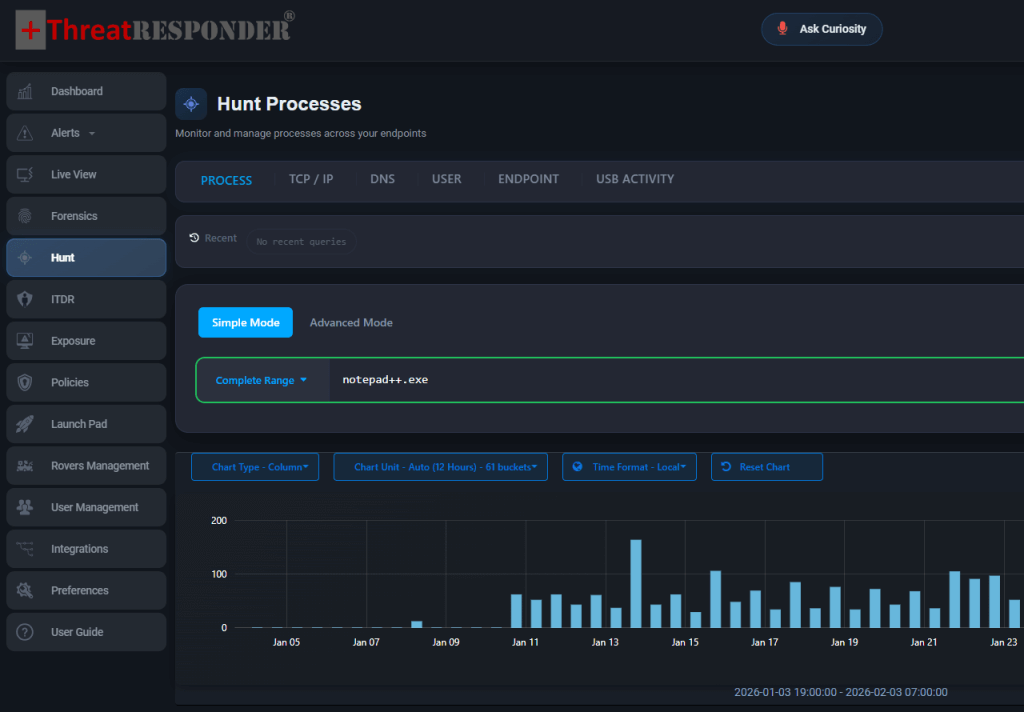

Hunt for IOCs exploiting Notepad++:

Figure: Hash based Hunt for Notepad++ Exploitation with ThreatResponder’s Simple Hunting Mode

Figure: Process based Hunt for Notepad++ Exploitation with ThreatResponder’s Advanced Hunting Mode

Figure: Hash based Hunt for Notepad++ Exploitation with ThreatResponder’s Advanced Hunting Mode

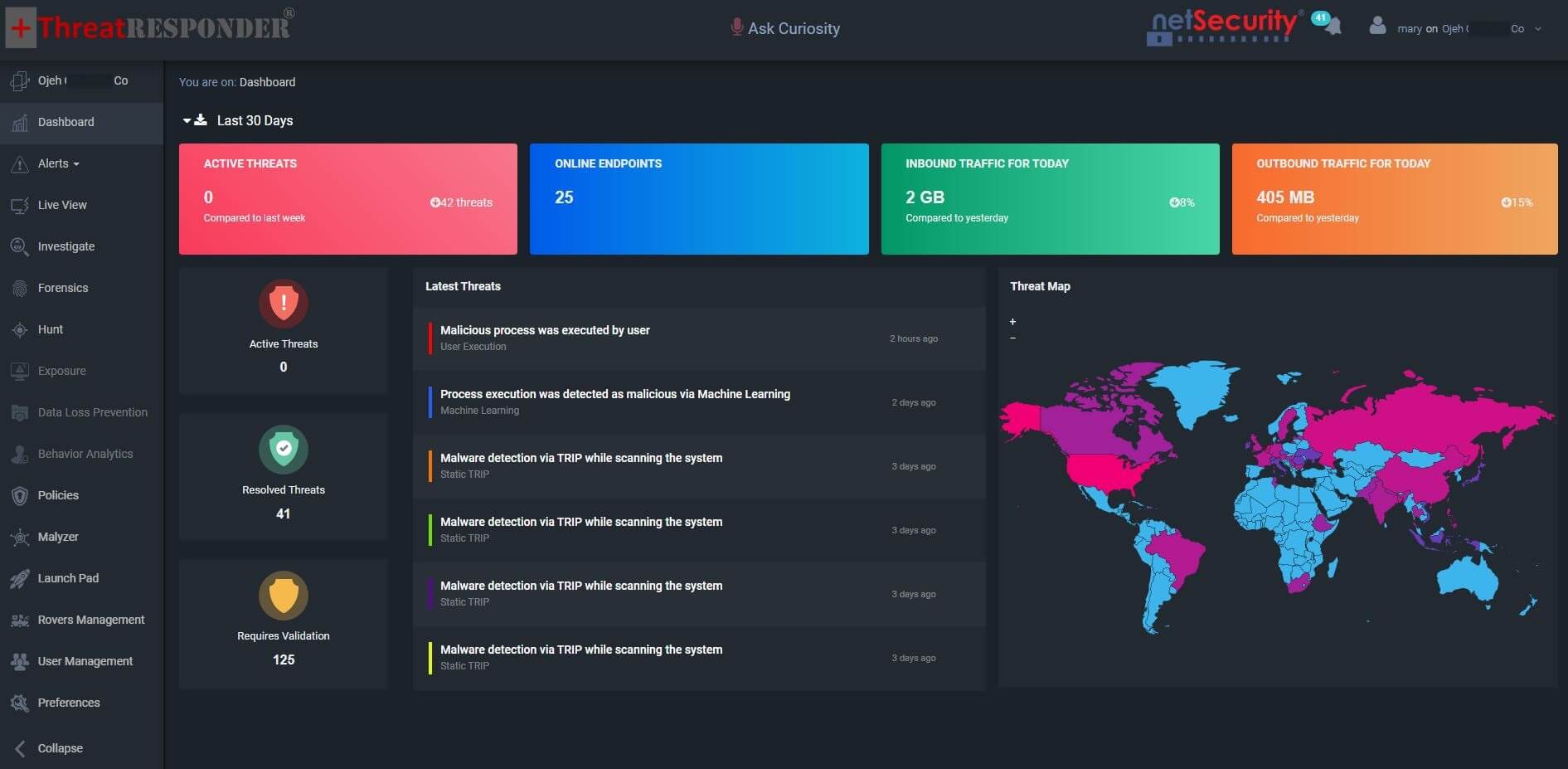

Rapid Containment and Automated Response with ThreatResponder

Once malicious behavior is identified, ThreatResponder enables immediate containment actions such as isolating the endpoint, terminating the abused process tree, and quarantining malicious dependencies. This reduces dwell time and prevents lateral movement while giving security teams the context needed to understand how the attack began and where it may have propagated.

By focusing on how attackers abuse trust rather than simply whether a file appears legitimate, ThreatResponder closes one of the most critical gaps in modern endpoint defense and stops attackers who rely on vulnerable legitimate software as their entry point.

Disclaimer

The page’s content shall be deemed proprietary and privileged information of NETSECURITY CORPORATION. It shall be noted that NETSECURITY CORPORATION copyrights the contents of this page. Any violation/misuse/unauthorized use of this content “as is” or “modified” shall be considered illegal and subjected to articles and provisions that have been stipulated in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL).